A museum exhibition review

By Cat McGuire

November 5, 2018

Overview

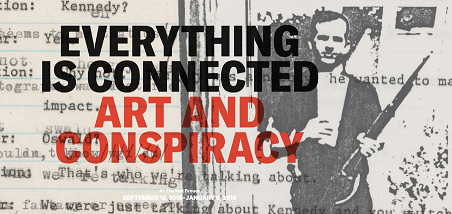

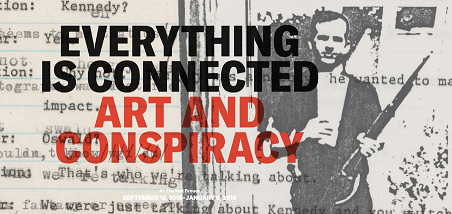

An exhibit called Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy is currently on display at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York at The Met Breuer. According to the curator, this apparently is the first time the art world has mounted a significant exhibition on the topic of conspiracies (even though much of the work presented is in The Met’s own collection).

The Met is arguably the high cathedral of culture in America—The New York Times of the art world if you will. Curious to hear their official perspective, on October 30, I got a ticket for one of the very few Exhibition Tours the show offered.

The one-hour walking lecture was led by one of the two curators, Douglas Eklund, Director of Photographs, who started work on the exhibit in 2010. He seemed proud of his prescience. Who knew eight years ago what a topical subject conspiracy theories would become?

That Eklund had been employed by The Met since the ‘90s tells me that this controversial subject had not been assigned willy-nilly. Eklund’s decisions surely had the full imprimatur of The Met. As such, for the purposes of my review of the show, fair or not, henceforth for me Eklund represents The Met incarnate.

Eklund was quite pleased by the sold-out crowd of 25 people, and several times during the tour remarked how no one was wandering away as tour goers often do. Almost everyone stayed with him to the end, indicating a strong degree of interest.

The exhibit features 30 artists and is divided into two distinct parts: theories that had proven to be largely true versus the Rabbit Hole (my capitalization, the show’s repeated use). The following explication from the entrance wall text does a good job of explaining the exhibit’s bifurcation:

The exhibition traces the simultaneous development of two kinds of art about conspiracy. Works based in historical research and investigative reporting open the show’s first half. The artists consider the factual nature of these works to be paramount. They uncover hidden layers of deceit beneath the bureaucratic complexity and often controlled media of postwar culture, hewing strictly to the public record to expose schemes such as the shell corporations of New York real estate investors and vast, interconnected networks encompassing politicians, businessmen, and arms dealers.

Works in the exhibition’s second half plunge down the rabbit hole, where facts and fantasy freely intermingle. No less thoroughly researched than those in the opening galleries, these works often aim to capture the interior ways in which people explain the world and their place in it with only partial information. Diving headlong into the fever dream of the disaffected, these artists create fantastical works that nevertheless unearth uncomfortable truths in an age of information overload and weakened trust in institutions.

The 3-minute video on the exhibit’s web page is worth watching both to see some of the art and to hear the curator’s spiel.

And now, on to the tour.

First Half of the Exhibit: Conspiracies Your Mom Could Believe

During the introduction to the tour, Eklund invoked “Trump” and “annus horribilis” in the same sentence in a way that assumed everyone present was in accord. Regardless of one’s political persuasion, I was taken aback that in a public setting a representative of a nonprofit institution would put forth such an overtly-biased, partisan point of view.

Eklund mentioned 9/11, but it was in reference to some other issue—versus being the issue itself. Given the theme of the show, the words “nine eleven” remarkably were never uttered by the man again for the rest of the tour.

Due to my pea-brain understanding of postmodern art, I found the first work to be the best display of art—as opposed to so many of the visual atrocities that I am convinced a third-grader could come up with. Before us were two eye-grabbing paintings of Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby by Wayne Gonzales which clearly referenced Andy Warhol’s iconic portraits.

In discussing the JFK assassination, Eklund said it will always forever be a mystery who killed Kennedy. Uh, no, the “mystery” meme is precisely the opposite of the JFK research community’s position. Those dogged investigators—some on the cold case over fifty years now—almost uniformly believe that if there were a trial, the forensic evidence is so voluminous, it would obliterate the Lone Gunman official story. (Since Eklund announced that between the first and second parts of the show he’d stop to take questions, I kept my mouth shut.)

Next up was the fascinating, complex, deeply researched work of Mark Lombardi. Go to the link. It’s worth examining his art, especially in light of the artist’s mysterious death. I was impressed Lombardi had been selected and assumed Eklund had read the definitive book on him, Interlock: Art, Conspiracy, and the Shadow Worlds of Mark Lombardi by Patricia Goldstone.

At a mobile installation Eklund related how Alexander Calder for years, like many abstract expressionists, was funded by the CIA in a skewed effort to weaponize art in service to the Cold War against the USSR. He didn’t mention it, but I’m sure that tidbit came from Frances Stoner Saunders’ important book, Who Paid the Piper?: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War.

For “communities in crisis,” there were videos about the Black Panthers, how they and the Left anti-war movement were targets of infiltration, and how the theft of FBI records eventually revealed the COINTEL program of government spying, thereby validating a widely-held conspiracy theory. Eklund described a painting of Ronald Reagan and the October Surprise as giving further credence to the veracity of other conspiracy theories.

Artwork by Hans Haacke likewise exposed conspiracy theories that turned out to be true. In this case, New York real estate deals. (Haacke helped advise the show. Many a day the septuagenarian rode his bike over to the museum to work on the exhibition.)

We eventually came to artwork focusing on Henry Kissinger, particularly his role in the Chilean coup d’état. Polishing his street cred, Eklund revealed that although Kissinger is a Met trustee, Met management did not interfere with the exhibition in general, nor the Kissinger installation in particular. (He added that the museum did, however, recently turn down some money from the Saudi government due to the Jamal Khashoggi murder.)

Bored with the obvious—I mean who doesn’t know Kissinger was palsy-walsy with Pinochet?—I wandered over to an artwork consisting of newspaper clippings with the prominent words “Red Brigade” and “Aldo Moro.” Now we’re talking. I eagerly approached the wall text.

It affirmed Leftist kidnappings and bombings in post-WWII Europe, yet nary a word about who was behind it all. The nebulous critique seemingly was about the power of the press to repeatedly whip up publicity of the ensuing violent chaos. That was it. Period. Hmmmm. . .

At another Oswald work, Eklund said the main obsession of JFK conspiracy theorists is Oswald’s double. Yeah, right, as if the entire research community is transfixed by John Armstrong’s controversial analysis, however spot-on it may be. Eklund mentioned Mae Brussel and Sylvia Meagher, whose name he incorrectly pronounced “meager,” not “mar,” which I duly noted. (Another JFK watchword: Murchinson is pronounced “murk,” not “murch.”)

Finally we got to the end of Part 1 and Eklund opened the floor to questions. I raised my hand and asked, “Was there a reason the Red Brigade piece made no mention of Operation Gladio?” Wide-eyed, open-mouthed, he goes, “Busted!! We have a conspiracy cognoscenti among us.”

He proceeded to confess to the crowd how it was only very recently that he learned about Gladio and he was most assuredly updating some of show’s materials, but, yes, yeah, unfortunately, this key piece—Operation Gladio—was indeed absent from the exhibit. He was sheepish and flummoxed that someone had discovered his glaring omission before he was able to fix it.

My god! The guy has been working on this exhibition since 2010 and only now discovered Gladio?! Such a telling blunder speaks volumes about the show’s curatorial myopia.

When people then asked “What is Gladio?” he pointed to me and said “I’ll let her tell you.” Startled to be given a platform, however minor, to speak truth at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, I summoned forth my best professorial manner, albeit my synopsis ended up rather disjointed:

“Operation Gladio took place in Europe after WWII. There were leave-behind troops during the Cold War, who were actually NATO and CIA, there to prevent the Communists and Leftists from getting public support, especially from being elected. Train stations were bombed in Brabant and Rome, and Aldo Moro, the Prime Minister, was kidnapped. It was all blamed on the Leftists, but it was really the CIA fomenting fear. And some people say Gladio is happening here today and that’s why we have all these bombs going off too.”

Wow! Did I actually say that?!

I would have loved to have gone on, but given that the pipe bombs and Pittsburg attacks were mere days ago, I figured I better get off my soapbox while the getting was good.

Eklund instantly said something like “There you have it! That’s where we are today!” In other words, “Voilà!” I was very relieved he didn’t exclaim something more derogatory like, “See, look. This is where conspiracy theorists take it.” As in “Move along, folks, this is clearly a Rabbit Hole spin.”

I honestly believe Eklund himself had not put two and two together. That despite all his research, this was the first time he became aware of a linkage between Gladio and our contemporary political landscape—and was thereby behind the curve in responding to the obvious connection. By then it was too late to unring the bell and dissemble any PR damage. My truther bombshell had already dropped.

One woman gasped at what I said, but it wasn’t clear if it was because I dared to say such a thing . . . or she was astonished by the recognition of what I had exposed. Another woman asked me how to spell Gladio. I was hoping more people would request information, but no one else did. At the end of the show, I heard someone at the elevator wonder, “Who is Aldo Moro?” “Is he Spanish?” A woman replied, “No, he’s Italian. Gladio was in Italy.” Perhaps some seeds were sown . . .

At this point Eklund finally brought up the CIA origins of the conspiracy meme. I consider it unconscionable that such pivotal evidence of the historical record is absent from the entrance wall text. While he was deconstructing the meme's roots vis-à-vis the Warren Report, I saw a nearby work consisting of blow-ups from an earlier typewritten era of two government memos riddled with signatures and official marginalia. I ambled over, convinced one would be the classic CIA conspiracy memo itself. Nope. Fat chance from this show.

I do not believe such a sterling Exhibit A was purposefully invisibilized. I honestly think Eklund—and the artist who depicted the two bureaucratic documents writ large—did not understand the paramount significance of the CIA memo. Clearly they had not read Lance deHaven-Smith.

Second Half of the Exhibit: Down the Rabbit Hole

Eklund noted that his research for the exhibit consisted of watching “the most gross, right-wing stuff on YouTube.” Well, Part 2 shows it. Not only was the art itself often phantasmagorical, but the content touched on everything from UFOs to the fake McMartin child sex abuse scandal in Los Angeles in the '80s involving recovered memories. While pointing out that Watergate opened up conspiracy theories, he also lectured on myths and religions and how anxieties are managed.

One installation depicted a grassy knoll scene littered in one spot with the detritus of snacks, meant to evince perhaps some bored gunman’s leave-behind garbage—which for all the world looked to me like little dog turds, but then what do I know about high art? Maybe the artist’s overly-inspired imagination was spurred on by what Eklund shared was a collaborative effort by himself, the artist, and others to install the piece. (“We had fun! We made martinis!”)

CalArts figured prominently in Part 2, with conceptual artist Mike Kelley’s work being a prime inspiration and to whom the show is dedicated. Eklund is from Southern California and revealed his mother was somewhat connected to the outer edges of the political scene there. Growing up, he remembered Manson, Esalen, UFOs, and more. I speculate to what degree wacky Lost Angeles from Eklund’s youth self-referentially informs this show.

Nonetheless, I believe the inclusion of the Rabbit Hole walk-on-the-wild-side of conspiracy theories is appropriate. That milieu definitely exists. To omit it would be in error. So I was patient and tolerant, but looking forward to seeing what kind of bow this was all going to be tied up into. I found the subjects of the last room’s three installations intriguing.

The first by Sarah Anne Johnson dealt with mind control. Her grandmother was a victim of the infamous CIA MK-Ultra experiments at McGill University in the early ‘60s entailing LSD, electric shock therapy, and sundry medieval psychological tortures. When Eklund in all seriousness said, “The CIA would never do this to Americans,” I looked at him with a flabbergasted expression that practically screamed, “Are you kidding?! What do you call Fort Detrick?!”

(Curiously, he mentioned “Wormwood,” the Errol Morris TV series about CIA agent Frank Olson’s “suicide,” which he surely knows is widely believed to be an Agency wetwork.)

As Eklund fumbled for the Canadian psychiatrist’s name, I piped up, “Dr. Ewen Cameron,” to which he promptly replied, “You know more than I do.” Ha! I'm not even the best of the best. Kevin Barrett, Barbara Honegger, James Corbett, or Graeme MacQueen for starters could run circles around this guy. As the curator, he was proof positive why our overlords’ institutions won’t let their minions debate truth activists.

The next installation by Jim Shaw was the grand facade of a building that you could actually enter. While the exterior conveyed the gravitas of a Corinthian-columned bank, cryptic symbols abounded. Inside a full-blown Rabbit Hole of Freemasonary was on display, flouting arcane secrets of enterprise fortune: black-and-white checkerboard-tiled floors, gnomes gathered around a manger scene giving birth to compound interest, towering crystal clusters, coded hand signals, and the ubiquitous evil eye.

At this point Eklund laughed, explaining that Shaw is indirectly commenting on that ultimate conspiracy theory: Soros, Hillary, and the Rothschilds are reptilians. Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha. He went on to explain that Shaw’s work speaks to how Catholics, Mormons, and Freemasons were once blamed for society’s ills—and now you can add Jews, and, oh, also the Illuminati. Say what? I got cross-eyed by that stew of confusion.

The third work was an upside-down, black-and-white photograph of Vince Foster's funeral, whose death under murky circumstances Eklund claimed is standard YouTube fare in which speculation abounds as to whether Foster was actually “suicided.” Can someone make sure Eklund gets a copy of the definitive book on the subject by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, the British investigative journalist and International Business Editor for The Daily Telegraph?

Eklund brought up another mysterious death of a drugged, married woman back during Watergate . . . He groped for her name. From that flimsy clue, I proffered, “Martha Mitchell?” “Yep,” he responded, by now blasé by my subject matter expertise.

He went into a postmodern riff on how there’s a collapse of belief in objectivity. That everyone now has their own individual reality. No one is who they seem to be. There are cut-outs everywhere. Pointing to me, he said, “I know you know what a cut-out is.”

The tour was basically over, but people wanted more and Eklund was game. Giddy might be more the operative word. He encouraged us to buy the catalogue (implying mission-critical reading), and marveled again that most of the tour members were still in attendance.

He asked if there were any questions. My hand predictably shot up: “Have you by chance read Conspiracy Theory in America by Lance deHaven-Smith?” To my great surprise, he answered in the affirmative. How I wondered could someone read such a paradigmatic book and mount a show whose research covered practically the entire gamut of conspiracy politics, and yet so readily accept at face value Official Narrative rationales?

He asserted that we have more pressing problems in this country than conspiracy theories. A woman responded that it’s only a problem if people believe them. “Yes!” he said. “All these ‘deplorables’ with their twisted beliefs are the problem.” Reducing entire swathes of history to right-wing nuts, on cue the recent attacks mirrored back to him this facile worldview. Heaven forbid one seriously deliberate the role of “patsy,” that perennial conspiracy character.

Another woman asked about fiat currency and the Yellow Brick Road metaphor from the Wizard of Oz? He complimented her on having discovered that path of the Rabbit Hole. She further queried who has the fix on all our money? Who is setting the gold standard? I suggested she check out the Federal Reserve and the BIS. “What’s that?” “The Bank for International Settlements in Basel.” “Oh, OK.” More seeds . . .

(Bonus factoid: The first chairman of the BIS was Gates McGarrah, the grandfather of Richard McGarrah Helms, Director of the CIA from 1966-73.)

My Two Cents

In reflecting on the show, I realized that the entire exhibit focused on the past. There was virtually no mention of the present-day epidemic of violence known in Gladio terms as a “strategy of tension.” After squeezing fascist mileage out of each successive “terrorist” attack, manipulated events like 9/11, Charlie Hebdo, the Boston Marathon, Orlando, Bataclan, San Bernardino, Las Vegas, Parkland, etc., etc. each become a blurred cog in the fear machine designed to bully a cowed populace into silent obedience.

Yet, while the show dealt directly with history, it could never be referred to as history because history is concerned with facts, and since so many of the actual facts are hidden and unmentionable, the events have to be deceptively defined as “conspiracies”—never history. The powers that be are waiting for each false flag’s saeculum to pass into the Memory Hole so that the faked history can assert itself as uncontested truth.

The New York Times reviewed the show on November 1 with the subdued titled, How Conspiracy Theories Shape Art, inadequately conveying their actual opinion. In the write-up, though, the newspaper of record outright called the show a “crackpot exhibition.”

If The Met presents our collective id’s subterranean rangy speculations, The Times can be depended upon to articulate what the ego’s official takeaway on conspiracy theories should be: “. . . the real hazard of today’s conspiracy theory boom is that it had smoothed the way for actual malfeasance . . .”

And this was the uniform messaging people on the tour were regurgitating. Trump and his deplorables are to blame! Off with their heads! Escalate the censorship! Eklund, the haut intellectual steeped deep in the actual data, likewise could not conceive of an alternative, transpartisan analysis for the ensuing violent chaos. Nor could he ably discern which key gems of evidence to pluck from the richness of history for public edification.

Having worked on this project for so many years, I thought perhaps in stumbling upon an individual who is his knowledge-base equal, maybe the curator would be interested in sharing notes with me? Au contraire. At the lecture’s end, without even so much as a good-bye, he sauntered off—presumably to ensure his own theories about conspiracies would not be contaminated by whatever might come out of my menacing mouth.

Bio

Cat McGuire is a progressive truth activist who lives in Hells Kitchen.